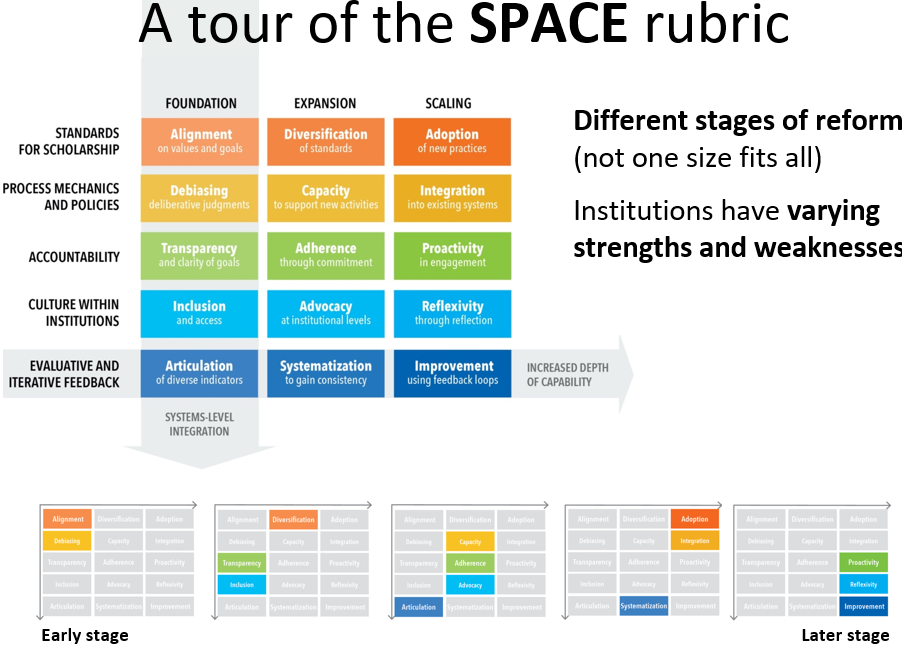

“Because every institution is different, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. With this in mind, the SPACE rubric was designed to be an adaptable tool. It supports institutions that are just beginning to consider improving their assessment practices, as well as institutions that have already developed and implemented new practices.“

The process of reforming academic assessment policies and practices is an endeavor that requires significant planning and effort. From getting started to iteratively improving and maintaining new practices, it is important for institutions to be able to gauge their progress toward reform in order to understand which next steps to take or where improvement is needed. To support institutions on their path toward change, DORA has developed a new tool: SPACE to evolve academic assessment: A rubric for analyzing institutional progress indicators and conditions for success (SPACE rubric). The SPACE rubric was developed in collaboration with Ruth Schmidt, Associate Professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology, who led the participatory design process.

To explore contexts for use and discuss the lessons learned during the creation and piloting of the SPACE rubric, DORA organized two community calls on July 1, 2021, and July 8, 2021. In the first call, a panel consisting of policy makers, early career researchers, and faculty shared what they learned while piloting the SPACE rubric with Anna Hatch, DORA’s Program Director, and Schmidt. Panelists included Rinze Benedictus of the University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands; Nele Bracke of the Ghent University, Belgium; Yu Sasaki of Kyoto University, Japan; Andiswa Mfengu of the University of Cape Town, South Africa; and Olivia Rissland of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, USA. On the second community call, Hatch and Schmidt engaged in an open discussion with the audience about learnings from the July 1 panelists.

Introduction and insights from the development of the SPACE rubric

Hatch and Schmidt highlighted key takeaways and feedback gained during the iterative development of the SPACE rubric. They found that academic institutions have different capabilities and conditions that impact their ability to implement reform. Because every institution is different, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. With this in mind, the SPACE rubric was designed to be an adaptable tool. It supports institutions that are just beginning to consider improving their assessment practices, as well as institutions that have already developed and implemented new practices. The SPACE rubric does this in two ways:

- Establish a baseline: The rubric can help institutions understand their capacity to support the development and implementation of new academic assessment practices. This can help institutions move forward with a more well-informed and targeted assessment reform plan that accounts for institution-specific challenges.

- Retroactively analyze current practices: The rubric can help institutions examine how different strengths or gaps in their conditions may have impacted the outcomes of concrete interventions targeted to specific types of academic assessment activities—such as hiring, promotion, tenure, or even graduate student evaluation.

To aid institutions in identifying their ability to implement or improve assessment policies and practices, the SPACE rubric provides five different dimensions for consideration:

- Standards for scholarship: How “quality scholarship” is defined and rewarded.

- Process mechanics and policies: How new practices can or have been incorporated into institutional policies.

- Accountability: How stakeholders are held accountable for upholding new assessment practices.

- Culture within institutions: How current and changing practices are perceived by stakeholders.

- Evaluation and iterative feedback: How the outcomes of new interventions are measured and how they are improved.

Additionally, Schmidt discussed the flexibility of the guidance offered by the SPACE rubric throughout the process of developing reform efforts. The rubric accounts for institutions that are:

- Establishing a foundation of research assessment reform that has a shared clarity of purpose across the institution.

- Expanding the development of new practices.

- Scaling new practices to accelerate uptake and continuously improve practices.

Lessons learned from piloting the SPACE rubric

To begin, panelists discussed their takeaways from piloting the SPACE rubric at their institutions. For those individuals who were at the beginning of the process of reforming research assessment practices at their institutions, the rubric appeared to hold the most value as a tool to understand which initial steps to take toward achieving a particular goal. Sasaki highlighted the importance of the rubric’s foundation-level guidance, particularly in the case of countries where national funding agencies have a strong focus on bibliometrics as quality indicators. Sasaki pointed out the rubric’s multiple uses in this context: First, the rubric outlines specific early steps needed to help catalyze change and avoid unforeseen pitfalls. Second, the rubric can serve as a discussion guide to help align the values of stakeholders. From a faculty perspective, Rissland thought the SPACE rubric helps to outline the order and priorities for how to discuss, advocate for, and implement reform. Rissland and Sasaki both pointed out the importance of having discussions that establish a core of shared values surrounding what needs to change in terms of research assessment practices. Mfengu affirmed the usefulness of the SPACE rubric for understanding how to gauge what stage of reform an institution is at as well as immediate goals to start implementing reform efforts.

For those whose institution was further along in the process to improve assessment practices, the rubric was found to be useful in several respects. Both Benedictus and Bracke said it helped guide a retrospective examination of reform efforts. In terms of expansion and acceleration, Benedictus found the rubric to be useful for identifying methods to scale current and ongoing efforts to improve academic recognition and reward systems.

Unexpected insights from using the SPACE rubric

In addition to the key lessons that panelists took away from piloting the SPACE rubric, they also discussed how the SPACE rubric revealed unexpected insights into institutional reform efforts. Bracke and Benedictus both spoke on the unexpected usefulness of the rubric as a tool to understand potential gaps in their progress. After identifying these potential gaps, they learned the rubric also provides suggestions to strengthen their current efforts moving forward. For example, the rubric highlights the usefulness of including a range of stakeholders (e.g., graduate students or other early career researchers, human resources department) when crafting new assessment policies and practices, which can help to create a more holistic and formalized approach toward reform.

Bracke also said the range of dimensions presented in the rubric helped her gain unexpected insight into how to engage different stakeholders. For example, some stakeholders may be more passionate about very specific processes rather than broad, institution-level efforts. This insight might be useful in helping to convince those who are skeptical of the importance of fair and responsible research assessment.

Mfengu noted an unanticipated insight from the rubric was the importance of identifying an “order of operations” when beginning the process of change. Specifically, the rubric outlines foundational steps (e.g., aligning and clearly articulating values) that seem simple but are critical for the success of future reform efforts. Mfengu found this insight particularly helpful, as it gave a clear indication of the importance of meeting initial goals.

One piece of advice to share with others to assist them in using the SPACE rubric

Rissland pointed out that iteratively developed tools help to make space for greater diversity of thought in terms of how to implement research assessment reform. Additionally, it is important to think deeply about “who is currently in the room and who should be in the room” when conversations are held about aligning values.

Included in the SPACE rubric resource is a worksheet that institutions may fill out to help conduct self-assessments and to gain an idea of what their next steps could be toward assessment reform. Bracke suggested that, when filling out the SPACE rubric worksheet, it would be helpful to do so deliberately and with a team from a diverse set of backgrounds (e.g., researchers, human resources). Mfengu highlighted the importance of contextualizing the rubric to specific departments and institutions. Benedictus also emphasized the importance of continually and iteratively aligning values on reform efforts throughout the development of new policies and practices.

Finally, Sasaki indicated the potential implications of the rubric beyond individual institutions. Currently attempts are being made to evolve the research assessment exercises at the national level in Japan. Initiating new assessment exercises at the national level presents challenges that are both unique and similar to those encountered when implementing reform at the institution level. Although the SPACE rubric was designed to be used by institutions, Sasaki also highlighted several aspects of the rubric that could be potentially relevant in the national context: ‘Standards for scholarship’, ‘Accountability’ and ‘Evaluative and iterative feedback’. Even in a different context, in this case national rather than individual, the common core issues covered by the SPACE rubric can still be useful when designing assessment systems.

Learnings from the second call

In both calls, we heard that “reforming institutional culture” was thought to be the most challenging dimension of the SPACE rubric to address. This result was not necessarily surprising given the discussion from the first community call and the recognized difficulty associated with culture change. We heard that the support of department leaders can help shift culture by demonstrating support for new assessment mechanisms.

Although this process is one that may seem slow, we learned it is important to acknowledge critical benchmarks of change that help shift culture no matter how small they might seem (e.g., increasing representation of minoritized groups among guest speakers and new hires). During the discussion, we found the rubric could be useful as a means to lower the barrier of entry for institutions by providing achievable low-risk goals and helping initiate discussions around reform.

Another question raised in the discussion was whether the SPACE rubric can support early career researchers advocating reform. We heard that the rubric can help early career researchers to identify and gather allies, align on values, and to advocate that discussions around reform be conducted transparently.

Haley Hazlett is DORA’s Program Manager.