A DORA Community Engagement Grants Report

In November 2021, DORA announced that we were piloting a new Community Engagement Grants: Supporting Academic Assessment Reform program with the goal to build on the momentum of the declaration and provide resources to advance fair and responsible academic assessment. In 2022, the DORA Community Engagement Grants supported 10 project proposals. The results of the Young researchers in action: the road towards a new PhD evaluation project are outlined below.

By Inez Koopman and Annemijn Algra — Young SiT, University Medical Center Utrecht (Netherlands)

Less emphasis on bibliometrics, more focus on personal accomplishments and growth in research-related competencies. That is the goal of Young Science in Transition’s (Young SiT) new evaluation approach for PhD candidates in Utrecht, the Netherlands. But what do PhD candidates think about the new evaluation? With the DORA engagement grant, we did in-depth interviews with PhD candidates and found out how the new evaluation can be improved and successfully implemented.

The beginning: from idea to evaluation

Together with Young SiT, a thinktank of young scientists at the UMC Utrecht, we (Inez Koopman and Annemijn Algra) have been working on the development and implementation of a new evaluation method for PhD candidates since 2018.1 In this new evaluation, PhD candidates are asked to describe their progress, accomplishments and learning goals. The evaluation also includes a self-assessment of their competencies. We started bottom-up, small, and locally. This meant that we first tested our new method in our own PhD program (Clinical and Experimental Neurosciences, where approximately 200 PhD’s are enrolled). After a first round of feedback, we realized the self-evaluation tool (the Dutch PhD Competence Model) needed to be modernized. Together with a group of enthusiastic programmers, we critically reviewed its content, gathered user-feedback from various early career networks and transformed the existing model into a modern and user-friendly web-based tool.2

In the meantime, we started approaching other PhD programs from the Utrecht Graduate School of Life Sciences (GSLS) to further promote and enroll our new method. We managed to get support ‘higher up’: the directors and coordinators of the GSLS and Board of Studies of Utrecht University were interested in our idea. They too were working on a new evaluation method, so we decided to team up. Our ideas were transformed into a new and broad evaluation form and guide that can soon be used by all PhD candidates enrolled in one of the 15 GSLS programs (approximately 1800 PhDs).

However, during the many discussions we had about the new evaluation one question kept popping up: ‘but what is the scientific evidence that this new evaluation is better than the old one’? Although the old evaluation, which included a list of all publications and prizes, was also implemented without any scientific evidence, it was a valid question. We needed to further understand the PhD perspective, and not only the perspective from PhDs in early career networks. Did PhD candidates think the new evaluation was an improvement and if so, how it could be improved even further?

We used our DORA engagement grant to set up an in-depth interview project with a first group of PhD candidates using the newly developed evaluation guide and new version of the online PhD Competence Model. Feedback about the pros and cons of the new approach helps us shape PhD research assessment.

PhD candidates shape their own research evaluation

The main aim of the interview project was to understand if and how the new assessment helps PhD candidates to address and feel recognized for their work in various competencies. Again, we used our own neuroscience PhD program as a starting point. With the support of the director, coordinator, and secretary of our program, we arranged that all enrolled PhD candidates received an e-mail explaining that we were kicking off with the new PhD evaluation and that they were invited to combine their assessment with an interview with us.

Of the group that agreed to participate, we selected PhD candidates who were scheduled to have their annual evaluation within the next few months. As some of the annual interviews were delayed due to planning difficulties, we decided to also interview candidates who had already filled out the new form and competency tool, but who were still awaiting their annual interview with their PhD supervisors. In our selection, we made sure the group was gender diverse and included PhD candidates in different stages of their PhD trajectory.

We wrote a semi-structured interview topic guide, which included baseline questions about the demographics and scientific background of the participants, as well as in-depth questions about the new form, the web-based competency tool, the annual interview with PhD supervisors, and the written and unwritten rules PhD candidates encounter during their trajectory. We asked members of our Young SiT thinktank and the programmers of the competency tool to critically review our guide. We also included a statement about the confidentiality of the data (using only (pseudo)anonymous data), to ensure PhD candidates felt safe during our interviews and to promote openness.

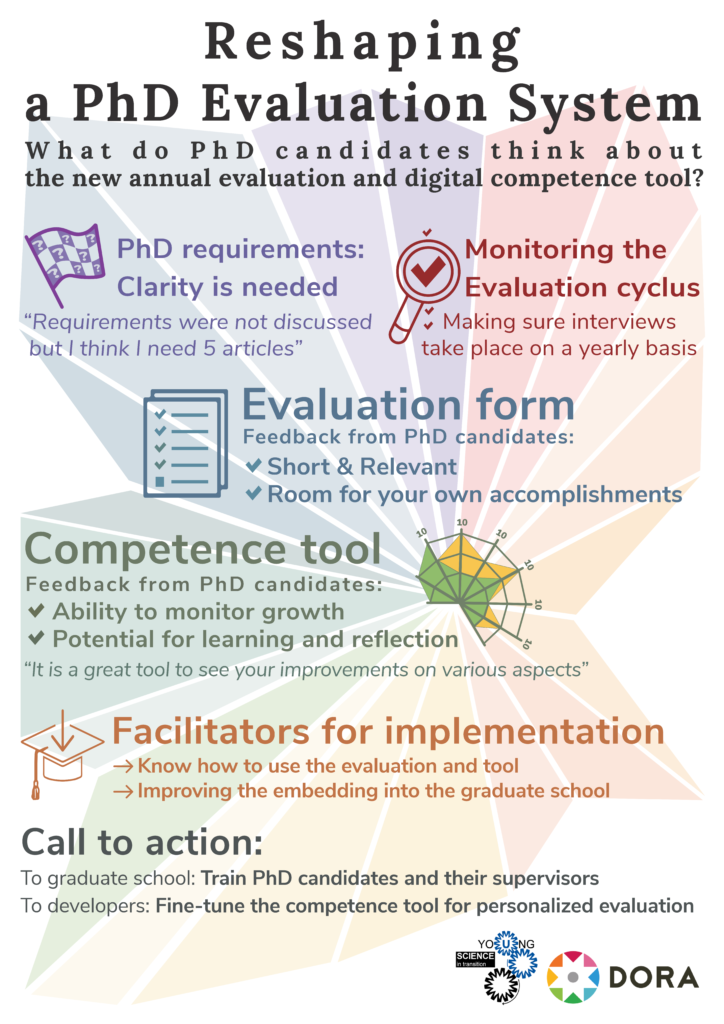

We recruited a student (Marijn van het Verlaat) to perform the interviews and to analyze the data. After training Marijn how to use the interview guide, we supervised the first two interviews. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed. Marijn systematically analyzed the transcripts according to the predefined topics in the guide, structured emerging themes and collected illustrative quotes. We both independently reviewed the transcripts and discussed the results with Marijn until we reached a consensus on the thematic content. Finally, we got in touch with a graphical designer (Bart van Dijk) for the development of the infographic. Before presenting the results to Bart, we did a creative session to come up with ideas on how to visualize the generic success factors and barriers per theme. The sketches we made during this session formed the rough draft for the infographic.

The infographic

In total, we conducted 10 semi-structured interviews. The participants were between 26 and 33 years old and six of them were female. Most were in the final phase of their PhD (six interviewees versus two first-years and two in the middle of their trajectory). Figure 1 shows the infographic we made from the content of the interviews. Most feedback we received about the form and the competence tool was positive. The form was considered short and relevant and the open questions about individual accomplishment and learning goals were appreciated. Positive factors mentioned about the tool included its ability to monitor growth, by presenting each new self-evaluation as a spider graph with a different color, and the role it plays in learning and reflection. The barriers of our new assessment approach were often factors that hampered implementation, which could be summarized in two overarching themes. The first theme was ‘PhD requirements’, with the lack of clarity about requirements often seen as the barrier. This was nicely illustrated by quotes such as “I think I need five articles before I can finish my thesis”, which underscore the harmful effect of ‘unwritten rules’ and how the prioritization of research output by some PhD supervisors prevents PhD candidates from discussing their work in various competencies. The second theme was ‘monitoring of the evaluation cycles’ and concerned the practical issues related to the planning and fulfillment of the annual assessments. Some interviewees reported that, even though they were in the final phase of their PhD, no interviews had taken place, as it was difficult to schedule a meeting with busy supervisors from different departments. Others noted that there was no time during their interview to discuss the self-evaluation tool. And although our GSLS does provide training for supervisors, PhD candidates experienced that supervisors did not know what to do and how to discuss the competency tool. After summarizing these generic barriers, we formulated facilitators for implementation, together with a call to action (Figure 1). Our recommendation to the GSLS, or in fact any graduate school implementing a new assessment, is to further train both PhD candidates and their supervisors. This not only exposes them to the right instructions, but also allows them to get used to a new assessment approach and in fact an ‘evaluation culture change’. For the developers of the new PhD competence tool, this in-depth interview project has also yielded a lot of important user-feedback. The tool is being updated with personalized features as we speak.

Change the evaluation, change the research culture

The DORA engagement grant enabled us to collect data on our new PhD evaluation method. Next up, we will schedule meetings with our GSLS to present the results of our project and stimulate implementation of the new evaluation for all PhDs in our graduate school. And not only our graduate school has shown interest, other universities in the Netherlands have also contacted us to learn from the ‘Utrecht’ practices. That means 1800 PhD candidates at our university and maybe more in the future will soon have a new research evaluation. Hopefully this will be start of something bigger, a culture change from bottom-up, driven by PhD candidates themselves.

*If you would like to know more about our ideas, experiences, and learning, you can always contact us to have a chat!

Email addresses: a.m.algra-2@umcutrecht.nl & i.koopman-4@umcutrecht.nl

References

1. Algra AM, Koopman I en Snoek R. How young researcher scan and should be involved in re-shaping research evaluation. Nature Index, online 31 March 2020. https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/how-young-researchers-can-re-shape-research-evaluation-universities