By David Mellor (Center for Open Science)

The Problem

There is widespread recognition that the research culture in academia requires reform. Hypercompetitive vying for grant funding, prestigious publications, and job opportunities foster a toxic environment. Furthermore, it distracts from the core value of the scientific community, which is a principled search for increasingly accurate explanations of how the world works. These values were espoused by Robert Merton in The Normative Structure of Science, 1942, in four specific principles:

- Communal ownership of scientific goods

- Universal evaluation of evidence on its own merit

- Disinterested search for truth

- Organized skepticism that considers all new evidence

The opposing values to these can be described as secrecy of evidence, evaluation of evidence based on reputation or trust, a self-interested motivation for conducting work, and dogmatic adherence to existing theories. The counternorms can be thought of roughly as an unprincipled effort to advance one’s reputation or the quantity of output over its quality.

The cultural barriers to more widespread practice of these norms of scientific conduct are well demonstrated in a study conducted by Anderson and colleagues in which they asked researchers three questions:

- To what degree should scientists follow these norms?

- To what degree do you follow these norms?

- To what degree does a typical scientist follow these norms?

They found near universal support for the first question, strong support with some ambivalence to the second, and strong belief that norms are not being followed by typical scientists in the third question.

Think about the implication of these findings. How likely would someone be to act selflessly (in accordance with scientific norms) when they perceive that every other scientist will act selfishly? One could not design an experiment in game theory to more quickly lead to universal adoption of selfish actions.

This is the situation in which we find ourselves and demonstrates the barriers to reforming scientific culture. It also explains why the failures to date to improve scientific culture have occurred—mere encouragements to reform practice, to evaluate evidence by its rigor instead of where it is published, or to expose one’s ideas to more transparency and scrutiny are frankly naive when faced with such deep impressions that it will be personally harmful to one’s career.

Getting to Better Culture

But in the dismal state in which we find ourselves, there is an effective strategy for reforming the conduct of basic, academic research. The end goal is a scientific ecosystem that practices the norms of scientific conduct: transparent and rigorous research.

We can take inspiration from the process by which cultural norms change in other parts of our society. In Diffusion of Innovations, Everett Rogers describes how the most innovative early adopters of new practices and technologies are a small minority of society that pave the way for early and late majorities of people to take them up. And of course there are always laggards who prefer to stick with previous versions for many years. The effect of this distribution of adoption is an initially gradual uptake of new techniques, which quickly accelerates as the phenomenon is picked up by the majority of people. This trend plateaus as the technique reaches saturation within the community.

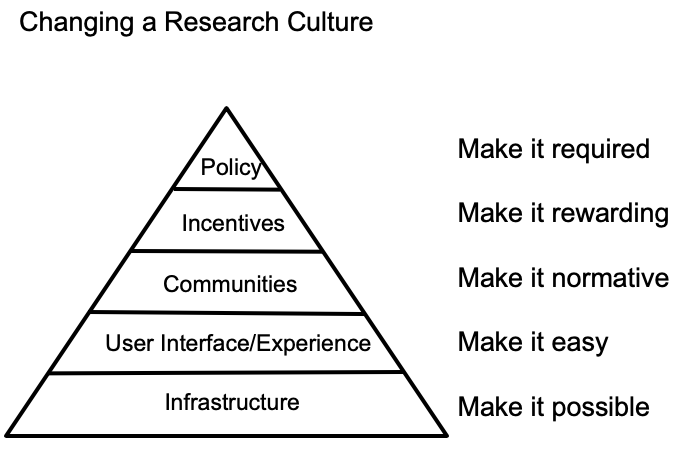

Rogers’ ideas can be transposed onto a strategy for culture change that is specifically relevant to a reform movement within the scientific community. Innovators will pick up a new, better technique as soon as it is possible. They represent the cutting edge of adoption and only a tiny minority of the community, however, which is mostly not yet ready to modify their workflows. As the new techniques become easier to use, however, early adopters will pick them up and integrate them into their workflows, seeing the benefits of the practice to their work. The great swell of adoption only begins as norms shift and it becomes visible for the majority of the community to identify these actions and begin to take them up. As recognition for accomplishment is the basic currency of scientific rewards (see, for example, the role of citations in academic stature), more adopters will take up a practice as it becomes a more recognized and therefore rewarded practice. Then the community is able to quickly rally behind updated policies that will codify such practices as bring required.

A Roadmap for Culture Change

This strategy lends itself to a series of specific initiatives that are useful for making this new culture a reality. Think of these initiatives as a roadmap for changing culture in the scientific community. Or, instead of treating the scientific community as a monolithic entity, take it as it is: a group of silos defined by disciplines—silos that are of course permeable as knowledge production increasingly relies on interdisciplinary efforts, but silos that are nonetheless rather resilient and reinforced by departments and academic societies.

The first necessary step is to make transparent and reproducible research possible with infrastructure to support it. The use of scripted statistical analysis software that makes perfectly clear how an analysis was conducted, online tools such as Github for collaborating and sharing this code, and hundreds of repositories that are helpful for storing the results of clear methods prove that reproducible research is possible. Depending on the exact procedure, it can take time to develop the skills to take these up, but practitioners know that this time is well spent in the overall efficiency gained by the reproducible workflow when it comes time to build upon recent work or onboard new members of the lab.

Improving the user experience for researchers and creating workflow spaces that are themselves repositories, as opposed to using end-of-life repositories that require curation and data cleaning prior to sharing, can make transparent and reproducible methods easier to implement and allow participation by more early adopters. An example of this is the OSF Registry that creates a project workspace where data and materials can be organized and, when the project is completed, shared as a persistent item in the repository

Shifting norms allow for researchers to see what current practices are widespread, to gradually shift expectations about what is standard, and to learn from what our colleagues are producing. These examples become the basis for one’s own work as we see and cite previous examples to model our own next steps. The adoption of open science practices such as sharing data, sharing research materials, and preregistering one’s study is now widely conducted, and that activity is visible to even the most casual observer of the field thanks to the table of contents of one of its most leading journals, Psychological Science.

Another example of shifting norms is the establishment of organizations in disciplines or geographic communities around these practices. The Society of the Improvement of Psychological Science and the UK Reproducibility Network are two such communities doing precisely that. These provide a venue for advocacy, for learning new methods, and for seeing the practices that the early adopters can share with the growing majority of practicing researchers.

Specific rewards can be accumulated by researchers for the activities that we’d like to see established. This will ensure that the ideal norms of scientific conduct are the precise activities that are rewarded through publication, grants, and hiring decisions. All three of these rewards can be directly integrated into existing academic cultures. Registered Reports is a publishing format in which the importance and rigor of the research question is the primary focus of scrutiny applied during the peer review process, as opposed to the surprisingness of the results, as is all too often the case.

The model can be applied to funding decisions as well, as is being done by progressive research funders such as the Children’s Tumor Foundation, the Flu Lab, and Cancer Research UK.

Universities have perhaps the most important role to play in furthering these conversations about rewarding ideal scientific norms. They can structure the job pathways so that transparent and rigorous methods are front and center for any evaluation process. Dozens of universities are doing this with their programs and job announcements. The essential element for these institutions is to ensure there is a clear signal that these activities are valued, and to back that up through decisions made based on adherence to these principles.

Finally, activities can be more easily required when the community expectations make policy change widely desired. The Transparency and Openness Promotion Guidelines (TOP) provide a specific set of practices and a roadmap of expectations for implementation. They include standards that journals or funders can adopt to require disclosure of a given practice, a mandate of that process, or a verification that the practice has been completed and is reproducible.

If not the impact, then how should evidence be evaluated?

There remains a gap in how recognition for scientific contributions should be recognized and rewarded. The most common metric remains the Impact Factor of a journal in which a finding was published. As DORA lays out eloquently, this is an inappropriate way to evaluate research. However, the Impact Factor remains an alluring metric because it is simple and intuitively appealing. There is, however, a better, more honest signal of research credibility—and that is transparency. The reason that transparency is a long-term solution for deciding which factor to use in evaluating research output is because it is necessary for evaluating the quality and rigor of the underlying evidence. And while transparency is not sufficient for evaluating rigor—it takes exceptional experience to fairly judge the details of a program and even sloppily completed science can be reported with complete transparency—it is the only way in which underlying credibility can be feasibly evaluated by peers.

Finally, transparency is a universally applicable ideal to strive for in any empirical research study. While no single metric or practice can be adopted by all research methods or disciplines, it is always possible to ask “How can the underlying evidence of this finding be more transparently provided?” If open data is not possible because of the sensitive nature of the work, protected access repositories can share meta-data about the study that describes how data are preserved. If the work could not be preregistered because it was purely exploratory or could not have been planned, materials and code can be provided that clearly documents the process by which data were collected.

The above roadmap for actions gives us an ideal way to expand transparent and reproducible research practices to a wider community of scholars. Research assessment is an essential component of the academic community, and transparency is the best viable path toward evaluating rigor and quality.