By Erin C. McKiernan (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), Juan Pablo Alperin (Simon Fraser University), Meredith T. Niles (University of Vermont), and Lesley A. Schimanski (Simon Fraser University)

Faculty often cite concerns about promotion and tenure evaluations as important factors limiting their adoption of open access, open data, and other open scholarship practices. We began the review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) project in 2016 in an effort to better understand how faculty are being evaluated and where there might be opportunities for reform. We collected over 800 documents governing RPT processes from a representative sample of 129 universities in the U.S. and Canada. Here is what we found:

A lack of clarity on how to recognize the public aspects of faculty work

We were interested in analyzing how different public dimensions of faculty work (e.g., public good, sharing of research, outreach activities, etc.) are evaluated, and searched the RPT documents for terms like ‘public’ and ‘community’. At first, the results were encouraging: 87% of institutions mentioned ‘community’, 75% mentioned ‘public’, and 64% mentioned ‘community/public engagement’. However, the context surrounding these mentions revealed a different picture. The terms ‘community’ and ‘public’ occurred most often in the context of academic service—activities that continue to be undervalued relative to teaching and research. There were few mentions discussing impact outside university walls, and no explicit incentives or support structure for rewarding public aspects of faculty work. Furthermore, when examining an activity that could have obvious public benefit—open access publishing—it was either absent or misconstrued. Only 5% of institutions mentioned ‘open access’, including mentions that equated it with ‘predatory open access’ or suggested open access was of low quality and lacked peer review.

An emphasis on metrics

The incentive structures we found in the RPT documents placed importance on metrics, such as citation counts, Journal Impact Factor (JIF), and journal acceptance/rejection rates. This is especially true for research-intensive (R-type) universities, with 75% of these institutions mentioning citation metrics in their RPT documents. Our analysis of the use of the JIF in particular showed that 40% of R-type institutions mention the JIF or closely related terms in their RPT documents, and that mentions are overwhelmingly supportive of the metric’s use. Of the institutions that mentioned the JIF, 87% supported its use, 13% expressed caution, and none heavily criticized or prohibited its use. Furthermore, over 60% of institutions that mentioned the JIF associated it with quality, despite evidence the metric is a poor measure of quality.

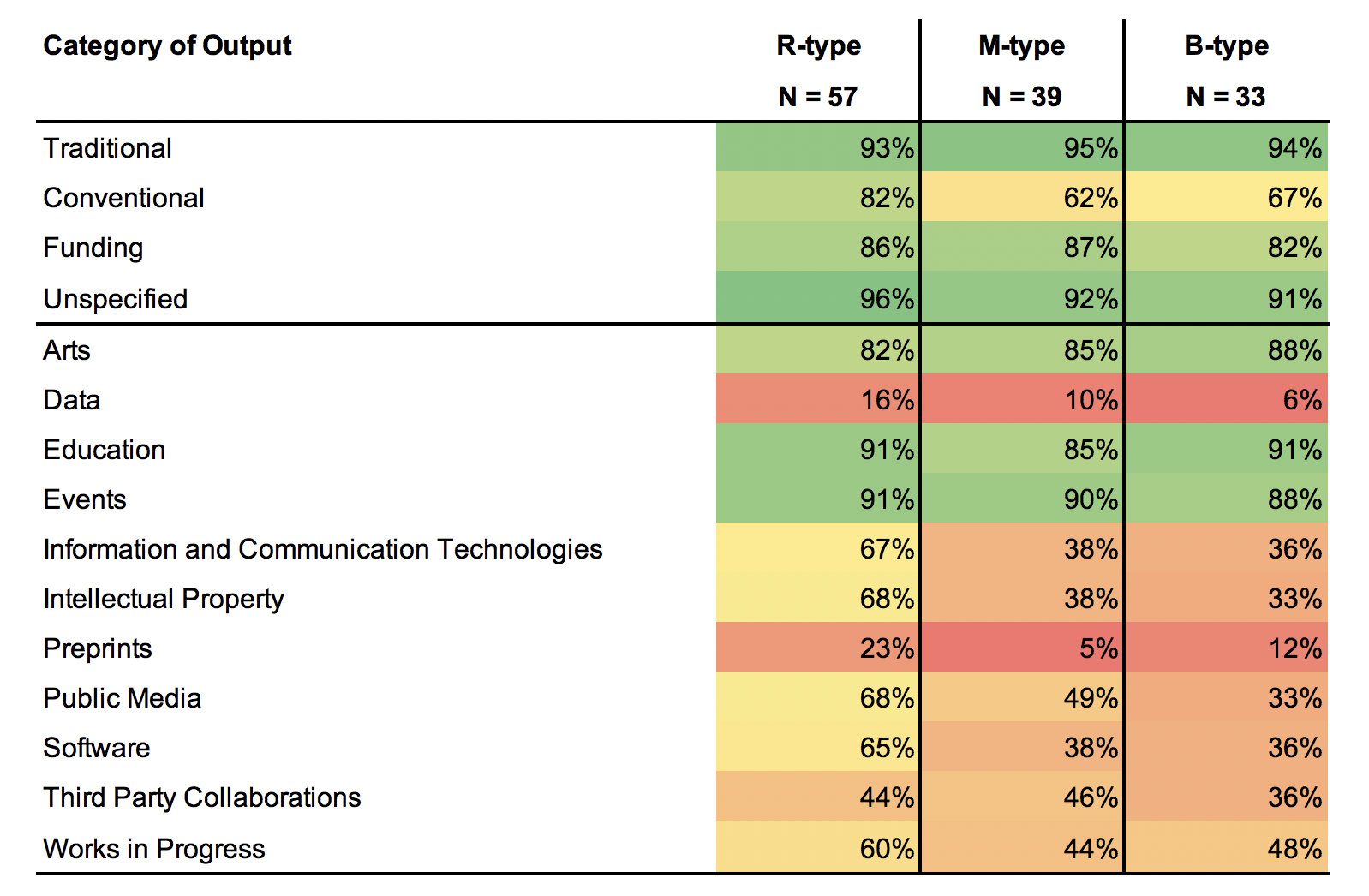

A focus on traditional scholarly outputs

Over 90% of institutions in our sample emphasized the importance of traditional outputs, such as journal articles, books, and conference proceedings. In contrast, far fewer institutions explicitly mentioned non-traditional outputs such as data (6-16%) and software (36-65%), or newer forms of scholarly communication like preprints (5-23%) and blogs that might be particularly important for communicating with the public. Even when these products were mentioned, it was often made clear they would count less than traditional forms of scholarship, providing a disincentive for faculty to invest time in these activities.

Faculty value readership, but think their peers value prestige

Analyzing RPT documents has given us a wealth of information, but it cannot tell us how faculty interpret the written criteria or how they view the RPT process. So, we surveyed faculty at 55 institutions in the U.S. and Canada, focusing on their publishing decisions and the relationship to RPT. Interestingly, we found a disconnect between what faculty say they value and what they think their peers value. Faculty reported that the most important factor for them in making publishing decisions was the readership of the journal. At the same time, they thought their peers were more concerned with journal prestige and metrics like JIF than they were. Faculty reported that the number of publications and journal name recognition were the most valued factors in RPT. However, older and tenured faculty (who are more likely to sit on RPT committees) placed less weight on factors like prestige and metrics.

Opportunities for evaluation reform

There are several take-home messages from this project we think are important when considering how to improve academic evaluations:

- More supportive language: We were discouraged by the low percentage of institutions mentioning open access and the negative nature of these mentions. There is a need for more supportive language in RPT documents surrounding the public dimensions of faculty work, like open access publishing, public outreach, and new forms of scholarly communication. Faculty should not be left guessing how these activities are viewed by their institution or how they will be evaluated.

- Words are not enough: Institutions in our sample mentioned ‘public’ or ‘community’, but had no clear incentives for rewarding public dimensions of faculty work. Simply inserting language into RPT documents without the supporting incentive structure will not be enough to change how faculty are evaluated. RPT committees should think about how these activities will be judged and measured, and make those assessments explicit.

- Valuing non-traditional outputs: Non-traditional outputs like data and software are often not mentioned, or relegated to lower status versus traditional outputs, providing clear disincentives. RPT committees should update evaluation guidelines to explicitly value a larger range of scholarly products across the disciplines. While some ranking of scholarly outputs is to be expected, some products clearly merit an elevation in status. For example, publicly available datasets and software may have equal if not higher value than journal articles, especially if wide community use of these products can be demonstrated.

- Deemphasizing traditional metrics: Traditional metrics like citation counts and JIF give just a glimpse (and sometimes a very biased one) into use by only a small, academic community. If we want committees to consider diverse products and impact outside university walls, we have to expand what metrics we consider. And we should realize that relying on metrics alone will provide an incomplete picture. RPT committees should allow faculty more opportunities to give written descriptions of their scholarly impact and move away from dependence on raw numbers.

- Discussing our values: Our finding that respondents generally perceive themselves in a more favorable light than their peers (e.g., less driven by prestige like JIF), elicits multiple self-bias concepts prevalent in social psychology, including illusory superiority. This suggests that there could be benefits in encouraging honest conversations about what faculty presently value when communicating academic research. Fostering conversations and other activities that allow faculty to make their values known may be critical to faculty making publication decisions that are consistent with their own values. Open dialogues such as these may also prompt reevaluation of the approach taken by RPT policy and guidelines in evaluating scholarly works.

Overall, our findings suggest that there is a mismatch between the language in RPT policy documents and what faculty value in publishing their research outputs. This is compounded by parallel mismatches between the philosophical ideals that tend to be communicated in RPT policy and other institutional documents (e.g., promoting the public nature of university scholarship) versus the explicit valuation of individual forms of scholarly work (i.e., little credit is actually given for sharing one’s scholarly work using venues easily accessible to the public). It seems that both institutions and individual faculty espouse admirable values—and it’s time for RPT policy to accurately reflect this.