Bias influences the decisions that impact academic careers, from peer review and publication to hiring and promotion. With these ongoing and systemic issues in mind, DORA’s June and July funder discussions focused on navigating system biases in decision-making. Ruth Schmidt, Associate Professor at the Institute of Design of the Illinois Institute of Technology, gave a presentation on how funders might address systems biases that affect funding decisions.

Address cognitive biases by reforming the system

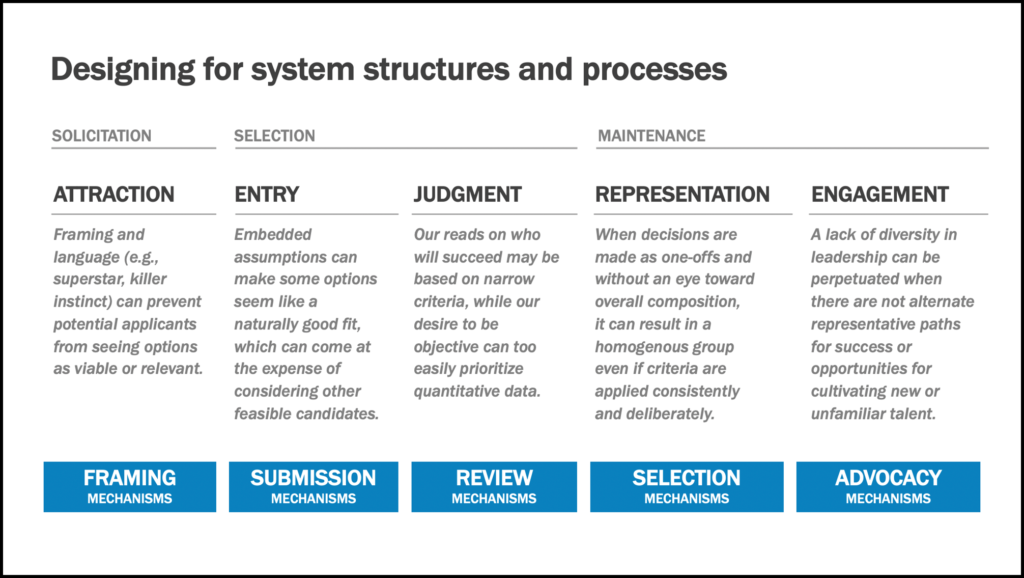

Biases influence decisions throughout all phases of the funding and assessment process: attracting applicants, entry into the applicant pool, judging applicants, representation at the leadership level, and engaging in new perspectives. According to Schmidt, the way an opportunity is presented or framed can prevent potential applicants from seeing it as a viable option. For example, specific language choices used in job solicitations—such as “killer sales instinct” or “superstar”—may prevent women from applying. Another example is “Status Quo Bias,” in which inherently biased “quality” indicators can become entrenched, leaving little room for new or innovative means of assessing applicants.

Schmidt noted that traditional approaches to addressing these issues, like implicit bias training at the individual level, are generally ineffective. She emphasized, instead, the need to create new conditions and systems for decision-making as a way to more effectively reduce bias. Addressing bias at a systems level lessens the reliance on individuals to reduce bias. In practice creating new systems might look like revising institutional processes for assessment. At each phase of the funding process, there are opportunities for systems level improvements:

- Framing: Attracting applicants

- Submission: Entry into the applicant pool

- Review: Judging applicants

- Selection: Representation at the leadership level

- Advocacy: Engaging in new perspectives

Commonly occurring systems-level biases

By understanding existing challenges stemming from biases, funders can address them appropriately. So Schmidt outlined commonly occurring systems-level biases for funders to keep in mind when considering reform:

1. Question the use of quantitative metrics and indicators

Quantitative indicators are viewed as a method to make quick, easy comparisons or seemingly credible determinations about value and are therefore appealing in situations where time and resources are scarce. Even though numbers carry biases, quantitative indicators seem more objective and create a sense of clarity about relative worth. In light of this, funders should be deliberate and informed when relying on quantitative indicators. According to Schmidt, potential ways to reduce the focus on quantitative indicators when assessing applicants could include explicitly asking for narrative content, inserting optionality into the application, or designating advocates among the reviewers to take pro/con positions regardless of a candidate’s bibliometric history.

2. Resist normalizing risk aversion

Schmidt discussed the challenge that risk aversion presents when considering whether to reform assessment practices to address biases. Examples of perceived risks might include the fear that reforming practices will take too much time and effort, or the fear that new practices will turn out to be ineffective. Additionally, risk aversion is amplified when decision-makers themselves are rewarded for adhering to old practices and norms. Along these lines, when attempting to manage risk, it is easy to overemphasize the reliability of past data that may not be as applicable to current situations. Older, more biased ways of assessing funding applications, for example, may be perceived as more credible or legitimate due to familiarity. Here Schmidt pointed out that it is always easier to not change rather than change. Therefore, it may be necessary to “lower the activation energy” required to implement change. This can be done by starting out with smaller, less risky, and more achievable changes to build toward larger and more risky changes.

3. Avoid neglecting a portfolio view

Schmidt highlighted the benefits of taking a portfolio view toward assessment, like capturing a more holistic picture of the candidate’s qualifications. There is value in looking at patterns to approach assessment with a deeper, more holistic view. Cluster hires, for example, can ensure building a critical mass of talent that takes the pressure off individuals to be the sole representative. Incorporating a portfolio view can reveal positive and negative aspects of an application that are obscured by assessing traits individually, and also help assessors recognize when a tendency to look for qualified applicants may inadvertently be selecting people all cut from the same mold.

4. Avoid prioritizing “shiny objects”

When assessing quality, it is easy to overestimate institutional affiliations or pedigree, past awards, and accolades as measures of current worth. In this case, historical success can reinforce the notion that association equals credibility. This assumption can sometimes distract reviewers from taking a deeper, more holistic look at applicants. A potential option to help remove these proxy substitutes for worth may be blinded applications (e.g., concealed applicant names, institutions where degrees were obtained, journal names). Doing this can help to more accurately evaluate attributes without the bias of name-recognition and prestige. Importantly, in fields of research that are smaller or more specialized, the efficacy of blinded applications may be limited due to the level of familiarity within the small group.

5. Question entrenched narratives about what makes sense and who belongs

Schmidt concluded by discussing the importance of recognizing and understanding implicit narratives that an organization, institution, or funder might unintentionally convey. For example, a wall of portraits of school deans who are homogeneous in terms of race and gender presents an implicit narrative about who succeeds, the school environment, and acceptance demographics.

Along similar lines, personal experiences can also introduce biases. For example, it is more comfortable to approve of a particular applicant if they look similar to the reviewer, remind the reviewer of themselves at a younger age, or have a similar backstory as the reviewer. This form of bias, a form of “anchoring,” unintentionally contributes to homogeneity. Anchoring can be minimized by purposefully creating diverse teams of reviewers with a diverse set of perspectives across seniority, expertise, experience, race, and gender. Additionally, it is important to simply recognize and begin to question when there are implicit narratives hidden in plain sight.

DORA’s funder discussion group is a community of practice that meets virtually every quarter to discuss policies and topics related to fair and responsible research assessment. If you are a public or private funder of research interested in joining the group, please reach out to DORA’s Program Director, Anna Hatch (info@dora.org). Organizations do not have to be a signatory of DORA to participate.

Haley Hazlett is DORA’s Program Manager.