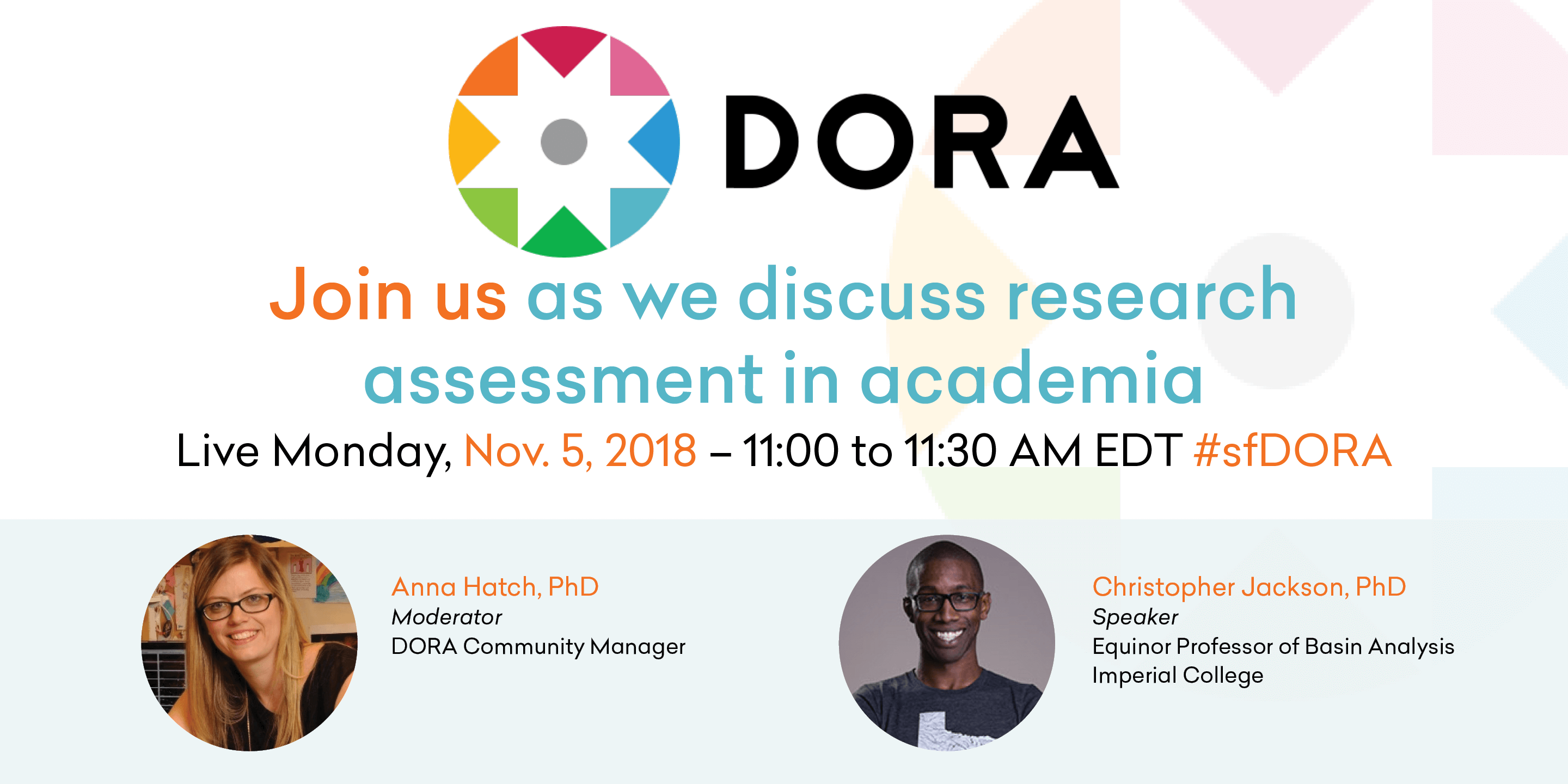

In academia, the bar for success continues to get higher for early-career researchers who are looking for faculty positions and grant funding. On November 4, we sat down with Prof. Christopher Jackson from Imperial College London to hear his perspective on the incentive structure in academia and what we can do better.

Before joining the academic ranks, Jackson worked as a researcher in the oil industry in Norway. One thing industry has in common with the academic world is the need to evaluate researchers for hiring and promotion. A drastic difference, however, is workplace culture. Unlike many universities, his company invested heavily in employee well being and maintained a positive work environment to ensure that staff could do their best research. This was good for business and improved the bottom line too. Jackson thinks institutions should adopt a similar approach to help academic researchers develop to their full potential.

Originally hired as maternity cover before joining the Imperial staff full-time, Jackson says he was largely unaware of the push for the use of responsible metrics until he started the promotion process and saw firsthand the bad behavior that metrics caused. It was also at that time he noticed the various routes someone can take through the promotion and tenure process. No review case is the same, because there are a lot of different ways that people can advance science. This can be difficult to recognize given the level of secrecy that is often associated with promotion and tenure. Jackson believes transparency could help. “If we have more transparency around the process, people would feel less like everything is going on behind closed doors.” It would build trust in the system, and researchers would better understand how their work is evaluated. To this end, he wrote a series of blog posts describing his review, promotion, and tenure journey, which he hopes will motivate others.

Cutting-edge research is only possible because of the less glamorous groundwork that happens first. Jackson believes that we need to recognize that the platform for major research advances is built by many people. He wants to see administrators value all contributions to research, including teaching and outreach activities. All of which allow science to move forward.

“Who we hire and whether we promote are hugely important decisions, and we should do due diligence on that process in the same way that we would when we collect some data that goes into a paper. That for me is the bottom line,” says Jackson. However, scientists manage multiple responsibilities and are increasingly pressed for time. Metrics and other shortcuts can ease the time burden. Jackson disagrees, “We need to give time and space for assessors to assess. They are bright people who are assessing bright people.”

Some of his greatest role models at the moment are not the people senior to him. They are early-career researchers, who understand the system in detail, are passionate, vociferous, and willing to take on senior managers. However, speaking up is a career risk, especially for young scientists. He wants to see established researchers doing more to introduce new policy.

Jackson admits that he thought metrics were a great thing before he learned how numbers can have built in judgments against sex, race, ethnicity, and location. His view on publishing has also evolved since signing DORA. “Now we think a lot harder about where we submit, we think a lot harder about who we review for, and we engage more with preprints.” In particular, he favors society journals because of the good they do for the broader community.